What it takes to do live music photography

Ever wonder what it takes to do live music photography? It takes practice, but I will do my best to share my tips with you.

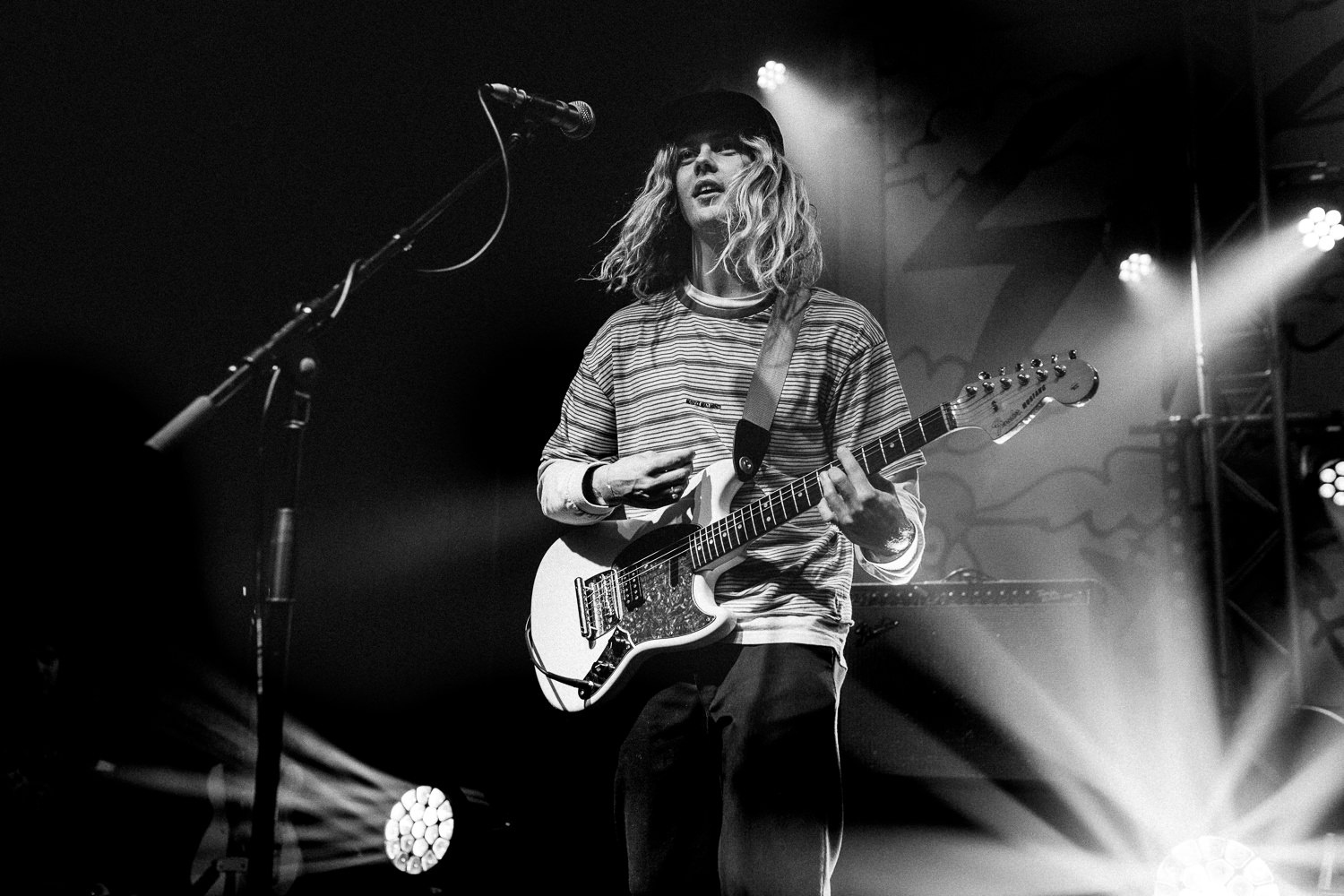

Matthew James Oxlade

I spend much of my time doing live music photography at gigs standing isolated. No beer being poured over my head, armpit sweat of singlet-wearing bogans assaulting my senses, or people threatening to fight me if I don’t give up my spot in the front row.

Where am I? I’m standing between the crowd and the artist in a designated area that helps me do my work as a concert photographer. This space doesn’t make me immune to the infectious energy of the show. It’s just different. You need to plan differently, think differently and act differently to the other sweaty bodies in the room.

Before I even thought I could shoot concerts, before I was even a Brisbane photographer working for anyone, I was a long time music lover. I wanted to have a role in the music industry, but I knew I couldn’t just become a music photographer the second I decided I wanted to take great photos at a concert. I had to learn how to make the most of my camera settings in a music environment to take concert photos that built a consistent portfolio.

A lot of people ask me how I got started shooting music festivals or with music photography as a whole. I hope I can help you get started with concert photography with the below ideas.

The live music photography planning

Assuming you’ve got a camera and the energy to stay out until 2am without the aid of drinks or party stimulants, you have all you need to get a photo pass. All you need is the pass itself. So how do you get it? You network.

The day a tour that I want to photograph is announced, I contact my primary choice for work, being whoever I want to submit the photos to. You should have a list of publications you like, admire and most of all, treat you right. The work you’ll be doing is most likely going to be unpaid with you working as a volunteer, which is why working for the right publication can make all the difference.

You want to arrive at the venue and trust that everything has been done to have your name on the door, and that if it isn’t, it’s not because the publication forgot or sent someone else’s name off instead of yours.

You’ll need to be familiar to the publication for them to grant you a photo pass. The number of times I’ve had someone in the venue come up to me in between bands and ask “How did you gain access to the photo pit? I have a camera at home and really like Skrillex.”

The answer I give is always the same, and I never get tired of giving it. “I shot a lot of bands that you’ve never heard of and will never get out of their parents’ garage.” It’s not all Eminem, Arcade Fire, Rolling Stones and Green Day for big music magazines. Getting you a photo pass for Grammy-winning bands is a big risk for the publication — they have relationships with a range of publicists that expect coverage, and a coverage of a certain quality.

Covering the smaller, local bands will give you a portfolio of music photography work that will gain you trust with the publications you are currently approved to contribute to, and ones you are wanting to contact about contributing to in the future. Part of your live music photography plan needs to be spending time with and being ok with shooting smaller, local bands.

Some publications will send a list of gigs they want covered out to their contributor list on a regular basis, while others work off a request basis. Assuming all other parts of your plan are in place, the publication will get back to you if they have pencilled you in to cover a gig. You’ll need to wait until they hear back from the tour’s publicist before you get your final confirmation.

I’ve been confirmed a month out from the gig date, and I’ve been confirmed on the day of a gig before. We all want as much notice as possible, but it’s important to stay committed to your date until you get final confirmation that you’ve been approved for a photo pass.

The live music photography thinking

That’s easy — I just need to pick which lenses I need, right? That’s important, but that’s not all.

Where are you shooting from? Only being permitted to shoot from the sound desk rather than a photo pit is becoming an increasingly popular stipulation on the promoter granting a publication a photo pass. Shooting from a sound desk sucks for a few reasons, the main being your angles are heavily restricted.

You’ll also miss those great showmanship moments the band will often throw if you’re right at their feet. Jim Lindberg of Pennywise grabbed my camera and photographed the crowd midway through their set at Soundwave. Shooting from a sound desk wouldn’t have permitted that. But if a sound desk shoot is all you’re allowed, there’s two things you need to do:

1. Accept it

2. Bring a zoom lens greater than 100mm

I shot A$AP Rocky at The Arena in 2013 and had a photo pass. I’m happy with the photos from the pit, but after the first three songs, I wanted to shoot more and so I moved to the crowd. I stood at the sound desk to gain some leverage over the crowd and equipped my 70–200mm.

Some of my favourite shots of that night came from the 150mm mark at the sound desk, and at least one of the photos appears in my live music portfolio at all times. The point: sound desks aren’t always horrible even if they aren’t the preference when shooting gigs.

Arrive at the venue early so you can cover the support bands. Shooting bands that aren’t the headliner is part of the deal, whether it’s explicitly said or not. I see this as a compulsory courtesy. The standard process for live music photography is that you’re allowed to photograph each band’s first three songs with no flash. That’s all you get because you’re a distraction between the audience and the band, so you’ll need to make your time count.

I use the mindset that you have two songs to shoot, because the first song is spent tracking and learning the lighting patterns or the lighting guy’s preferences. Shooting live shows and hoping for the best is as frowned upon as you imagine, and if you think through the performance during the first song you’ll walk out with better shots than if you just ‘spray and pray’ — I can almost guarantee it.

The live music photography acting

You’re working. You’re not playing. It’s easy to get caught up in the moment and thinking “Hey, I’m not getting paid so let’s just ball out with the homies and get turnt while we watch Kendrick Lamar do his thang!” Whether you think you’re safe to vomit on yourself in the corner or not, you can’t justify turning work into play. Here’s my take on the different styles of people you’ll encounter:

The playing bands

They are there to play, and anything else is a bonus. They don’t owe you anything in particular, which I’ll discuss at the end of this article.

The venue security

These guys are your friends, but they don’t want to hear your life story or let you backstage. Your pass has stipulations on where you can access (almost always the photo pit only), and security don’t have the authority to change that or grant additional access. Tip: When a kid comes crowd surfing over the barrier, it’s these guys that will slap the foot away from the back of your head, whether you’re aware of it or not. So they get my utmost respect.

The diehard fans

If you take a drink into the pit, you can count on someone asking for a sip. Chances are, if you’re as sober as you should be, you’ll be able to make an excuse that is satisfactory. Tip: I like to take their photo to give some variety to the photos I’ll submit, plus it gives you an opportunity to encourage the fans to check out your music photography work once they’ve recovered from their hangover the next day.

The venue staff

Venue staff are there to serve drinks and make the show run. They don’t prioritise live music photographers when waiting for a drink, because you’re not working or contributing to the venue in any way. Tip: Don’t waste your time waiting in the ‘No Service Area’ wearing your photo pass proudly.

The other photographers

These people are your friends, not your competitor. You are all there with photo passes, so take the time to say hello and have a chat.

The conclusion

Sounds like that will give you every chance in the world of walking away with some great shots, right? Let me leave you with the reason I keep shooting and never beat myself up.

In 2013 I shot Brian Jonestown Massacre, of DIG! fame. By far the worst gig I’ve ever shot. Everyone came to see Anton Newcombe, and he knew it. The lights dim. The crowd screamed as the band took to the stage and the lights beamed down on them. But where was Newcombe? It took two songs before I recognised him, because deep in the shadows, behind a speaker stack was a bleary-eyed Newcombe — effortlessly strumming away and mumbling into the microphone when necessary.

I could easily argue that Newcombe didn’t take the stage that night. He played his guitar from the shadows side of stage, making him impossible to shoot. I would argue he wasn’t even on the stage. The band did a great job, but it reminded me that bands aren’t playing for us to shoot — so no amount of planning, thinking or acting a certain way will guarantee you photographs of your favourite band. Shoot as a fan first, photographer second.